Childrenfs

Behavior

Problems and University Student Volunteer Work

at Schools: Focusing on

Children from China

Yuan

Xiang, Li, Tokyo Gakugei

University;

Hideki Sano, Tokyo Gakugei University

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

In the 80s, the Japanese government

planned to accept 100,000 foreign students. In the 90s, other types of

people

such as foreign laborers, and people in international marriage started

coming

to Japan. The number of children of

minority

decent suddenly increased but Japanese schools were not ready for it.

Japan had

little experiences in accepting immigrants and its schools had no

special

teachers for foreign children. Teaching methods and materials were made

on

trial and error base.@ In

order to grasp the situation, the government started a survey on

Japanese

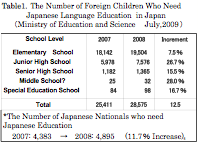

language education for foreign children. The Table1 shows the number of minority children in Japanese schools

over the

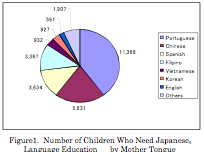

past two years. The figure1 shows the number

of foreign children who need Japanese language education in

2008. They

are grouped by their mother tongue.@ Portuguese 11,386, Chinese

5,831, Spanish, 3,634 and others, 7,724.@ The portion of top three

languages is about 70%.

In the past, Japanese language education

is the central task for newly arrived children. Recently, guidance for

higher

education is also an important task.@ However, due to such reasons as unstable

employment for foreigners and possible relocation, foreignersf lack of

knowledge about schools in Japan, and its educational system, some

foreign

children are not getting the kind of educational instruction they need.

On the

other hand, because of their low basic ability in the Japanese

language,

mathematics, English, and science, some children cannot pass high

school

admission tests. Even if they are admitted, many drop out of school

because of

a lack of adequate support or personal maladjustment.@ 97% of Japanese children

go to high

school, where as only 50% of foreign

children

in Japan do.

There are about 5,800

Chinese

children living in Japan.@ Their

parents have a

variety of visa status, such as war orphans, laborers, student visa and

spouse

visa by marriage. Often, the children lived away from parents.@ In recent

years, because some Chinese remarry to Japanese, their

children have new and challenging family environments with

cross-cultural

conflicts.@ Many parents

with less than enough

Japanese language skills do not know enough about Japanese schools and

its

education systems. It is only when their children come

that they find

out how difficult it is to educate children in Japan.@ Japanese

school start in March, whereas Chinese schools start in

June.@ Children who

finish junior high

schools or are older than 15 years of age are not admitted to

Japanese junior high schools, nor can they pass the difficult exams

necessary

to enter high school, which is selective, not compulsive.

@

From their arrival, children with low ability

easily feel helpless about learning because of the language barrier in

addition

to differences in school subjects.@ Due to

complex family

environments such as unstable parentsf visa status, children cannot

receive

proper support from their parents. They face culture shock and future

uncertainty.@ Moreover,

schoolteachers are not able

to support psychologically and study.@ Children who

could not

adjust to the new environment, lose self –confidence, become

internet-dependent, depressed, refuse to go to school, and exhibit

anti-social

behaviors.

Although

educational

support for foreign-born children is an urgent task, it is very hard

for busy

teachers to guide and support them.@ Most

qualified supporters

are people who understand the childfs cultural background and mind and

can give

care to them.@ Few people like this exist.@ In order to

solve this problem, we must consider options as to

gwho can help as well as when and how.h One approach started

several years ago to help lessen this problem was to have Chinese

college

students lend support to the Chinese children.@@ These

students teach Chinese children at public schools or NPO

schools as volunteers.@ Their main

activities of

support are in the area of Japanese language learning, translation in

classrooms, and counseling.@ Depending on

the necessity,

they help bridge the communication gap among teachers, children and

parents.

College students share their

culture and

educational background with children and easily form close

relationships.@ Many children

are open with

these students. In turn, the volunteer students can discover

psychological

problems and learning difficulties. Thus, Chinese students can help

teachers

improve their teaching methods.

Even though students are

very valuable, their support must be done under supervision: student

volunteers

must follow rules and teachersf directions and not make their own

judgments.@ Students

encounter a variety of tasks and situations at school,

for example, corroborating with teachers, studentsf privacy, difficult

cases,

time, and others.@@ It is

important not to withhold

information about the problem and always report to the teacher and

supervisor.@ The student

volunteers attend case conferences and confer with

college advisers.

Foreign students, as a

mentor, can give courage and hope by helping language learning and

cross-cultural living.@ On the other

hand, for

college students who mainly study and part-time work, this kind of

volunteering

is a social act or contribution that can help the volunteer grow.